This information can also be viewed as a PDF by clicking here.

The information provided is taken from various reference sources. It is provided as a guideline. No responsibility can be taken by the author or the Breastfeeding Network for the way in which the information is used. Clinical decisions remain the responsibility of medical and breastfeeding practitioners. The data presented here is intended to provide some immediate information but cannot replace input from professionals.

- Feeding with artificial formula in the first 4-6 months of life increases the risk to cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) compared to exclusive breastfeeding (Vandenplas et al 2007)

- 0.5% of exclusively breastfed infants show reactions to cow’s milk protein compared to 2%-7.5% of formula fed infants. (Vandenplas et al 2007)

- If a breastfed baby is thought to have CMPA the mother should eliminate all sources of cow’s milk from her own diet as well as that of her baby for a minimum of 3 weeks. Although improvement may be seen after 3 days it may not resolve for 4 weeks (Ludman et al 2013)

- A breastfeeding mother who is on a diet free of cow’s milk protein she should be prescribed a supplement of 1000 mg of calcium and 10 microgramme of vitamin D every day. (Ludman et al 2013)

Cows’ milk allergy can often be recognised and managed in primary care. Patients warranting a referral to specialist care include those with severe reactions, faltering growth, atopic comorbidities, multiple food allergies, complex symptoms, diagnostic uncertainty, and incomplete resolution after cows’ milk protein has been excluded (Ludman 2013).

Cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) can affect people of all ages but is most prevalent in infants, affecting between 2 and 7.5% of formula fed and 0.5% of exclusively breastfed babies. Exclusively breastfed babies develop CMPA as a result of milk proteins from products the mother has eaten transferring through breast milk. The level of cow’s milk protein present in breast milk is 100,000 times lower than that in cow’s milk. Most reactions to cow’s milk protein in exclusively breast fed babies are mild or moderate and severe forms of CMPA very rare. It is thought that immunomodulators present in breast milk and differences in the gut flora of breastfed and formula fed infants may contribute to this. (Ludman 2013).

Secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) in breastmilk “paints” a protective coating on the inside of a baby’s intestines to prevent penetration by potential allergens such as foreign proteins. SIgA cannot be replicated in formula.

The reaction may be mediated by IgE (anaphylaxis, urticaria) if they occur immediately following consumption of cow’s milk protein or non IgE (GI reactions, eczema, GOR) which may occur several hours or even days after consumption. The immune system responds to the protein casein or the whey found in cow’s milk.

Although these symptoms may be related to other conditions, they are likely to be due to CMPA if the severity is related to a change in the amount of cow’s milk consumed by the mother and/or baby, or if cow’s milk based formula or other similar foods are introduced into the baby’s diet. CMPA is also a likely cause if the symptoms appear in more than one system, for example diarrhoea and atopic dermatitis, and also if these symptoms are resistant to treatment. It is important to consider all outcomes and to take a full medical history to ensure that the symptoms are not due a cause other than CMPA. (Ludman 2013). Attention should also be paid to optimising attachment and frequent feeding if the baby is breastfed.

Where CMPA is suspected in a breastfed baby, the recommended treatment is for the mother to remove all sources of products containing cow’s milk from her diet, ideally under medical supervision. Mothers should be prescribed a supplement of 1000mg of calcium and

10 microgrammes of vitamin D every day.

| Organ involvement | Symptoms |

|

Gastrointestinal tract |

|

|

Skin |

|

|

Respiratory tract (unrelated to infection) |

|

|

General |

|

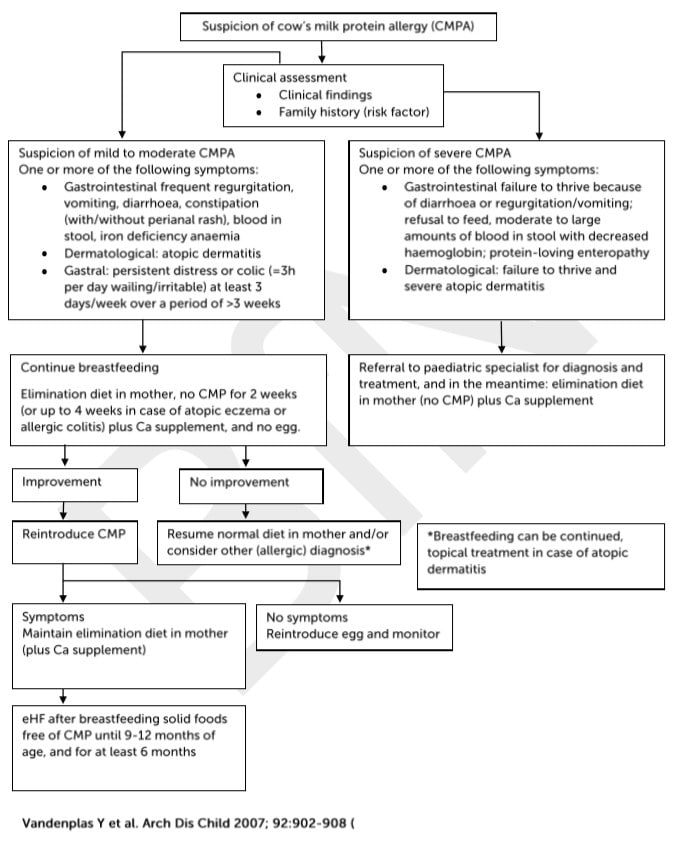

Algorithm for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) in exclusively breast-fed infants. (eHF= extensively hydrolysed formula.)

Vandenplas et al (2007) state that 10-35% of infants with CMPA have adverse reactions to soya. While Ludman et al (2013) report that up to 60% of patients with non-IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy and up to 14% with IgE mediated allergy also react to soya.

Where solid foods have been introduced, all sources of products containing cow’s milk should also be removed from the baby’s diet. It will usually take between 2 and 4 weeks for symptoms to disappear. It is suggested that milk is then reintroduced to ensure that this has been the cause of the symptoms. (Ludman 2013, NICE 2011).

Where a diagnosis of CMPA is confirmed the mother should avoid cow’s milk products in her diet for as long as she is breastfeeding. She will continue to require support to manage her nutrition, particularly where the elimination diet is over an extended period of time. A dietician or other healthcare professional managing the case will recommend at which point reintroduction of cow’s milk should be trialled and how this should be managed. Care should also be taken with the weaning diet and appropriate alternative sources of calcium included under dietetic supervision.

There is generally no need to add special prescription formula or soya formula. The baby can continue to receive breastmilk even whilst his/her mother is beginning to eliminate cow’s milk protein from her diet.

A diagnosis of cow’s milk protein allergy has many ramifications for mother and baby. A mother should not be asked to remove products containing cow’s milk protein lightly e.g. to resolve colic symptoms, without first considering referral to a breastfeeding expert to address issues around optimal attachment.

Update 2019

In a BMJ article in 2018 Dr C Van Tullekan suggested that the diagnosis of CMPA is a trojan horse for formula milk manufacturers to forge relationships with healthcare professionals under the guise of education. He noted that “Between 2006 and 2016, prescriptions of specialist formula milks for infants with cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) increased by nearly 500% from 105 029 to over 600 000 a year while NHS spending on these products increased by nearly 700% from £8.1m to over £60m annually. Epidemiological data give no indication of such a large increase in true prevalence—and the extensive links between the formula industry and the research, guidelines, medical education, and public awareness efforts around CMPA have raised the question of industry driven overdiagnosis. Nigel Rollins from the World Health Organization’s department of maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health agreed that “It’s reasonable to question whether these [prescription and spending] increases reflect a true increase in prevalence.”

It would be easy to identify virtually every child with symptoms in the table above. This does not imply that every day has CMPA although an exclusion diet is recommended to many mother “just to see if it helps”. The repercussions from diagnosis cannot be underestimated for the mother, the baby and the health economy. A diagnosis can be made only by excluding cows’ milk protein from the maternal diet, observing symptoms, and then reintroducing. Many mothers are willing to go to any lengths to maintain breastfeeding although others may perceive their milk as toxic to their baby and stop breastfeeding. Many support organisations and guidelines are written by industry sponsored sources and therefore seen as likely to influence perception of symptoms. Conflict of interest with organisations such as Nutricia should be taken into consideration when interpreting information.

Dr Helen Crawley First Steps Nutrition booklet Specialised Infant Formula (2018) notes that:

- Amino-acid based infant milks contain protein in the form of individual amino acids and are marketed to be used in the dietary management of moderate to severe cows’ milk protein allergy or multiple allergies. Amino-acid based infant milks are unlike other hypoallergenic infant milks in that they contain amino acids which are synthetically derived, as opposed to peptides originating from cows’ milk, meat or soya as found in extensively hydrolysed formula.

- These milks are about three times more expensive than extensively hydrolysed formula milks, and are an area in which cost savings to the NHS can be made with use of appropriate prescribing.

- Breastfeeding is the optimal way to feed a baby with cows’ milk protein allergy, with individualised maternal elimination of cows’ milk protein foods and fluids, and with adequate calcium and vitamin D supplementation to meet the mother’s nutritional requirements during breastfeeding.

- Amino-acid based infant milks are low in lactose or are lactose-free and contain maltodextrin or dried glucose syrup as the main carbohydrate source, meaning that oral care is particularly important for individuals being given these products.

References

- Crawley H Specialised Infant Milks in the UK 0-6 months. First Steps Nutrition 2018 https://www.firststepsnutrition.org/composition-claims-and-costs

- LIFIB Cows’ Milk Protein Allergy Briefing Paper Oct 15 http://lifib.org.uk/cows-milk-protein-allergybriefing-paper-oct-15/

- Ludman, S., Shah, N., Fox, A.T. Managing Cow’s Milk Allergy in Children BMJ 2013; 347:f5424

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2011) Food allergy in children and young people Diagnosis and assessment of food allergy in children and young people in primary care and community settings

- Van Tulleken C Overdiagnosis and industry influence: how cow’s milk protein allergy is extending the reach of infant formula manufacturers. BMJ 2018;363:k5056

- Vandenplas, Y., Brueton, M., Dupont, C., Hill, D., Isolauri, E., Koletzko, S., Oranje, A.P., Staiano, A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants Arch Dis Child 2007; 92:902-908

Competing interests of referenced papers

Vandenplas et al declared funding “Funding: The consensus panel, the literature search and the drafting of the manuscript were funded by a grant from SHS/Nutricia. The paper was drafted by Mark Greener, a medical writer. SHS International Ltd and Nutricia did not have any editorial control over the final manuscript, which remains entirely the responsibility of the authors. Competing interests: DH, CD, MB, SK and YV declare they have received support for clinical research projects from SHS/Nutricia and the same authors and MB declare they have presented lectures at SHS/Nutricia-sponsored meetings. Also, SK has presented lectures at sponsored meetings and received support for scientific work from Mead Johnson and Nestle. YV has received support from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Astra, Wyeth, Biocodex and Nestle. None of the other authors made any declarations relevant to the preparation of this manuscript. The authors declare the absence of competing interests and confirm their independence regarding the content of this manuscript.

Ludman et al We declare the following interests: ATF has done consultancy work for Mead Johnson Nutrition Danone, Nestle Nutrition,and Abbot. He has received fees for lectures or producing educational material from Mead Johnson Nutrition and Danone. He is site principal investigator for a Danone sponsored study funded through Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London.

©Dr Wendy Jones MBE, MRPharmS and the Breastfeeding Network Sept 2019